Introduction

The last few years I’ve been working in several SOA related projects, small projects as well as quite large projects. Almost all of these projects use a Canonical Data Model (CDM). In this post I will explain what a CDM is and point out what the benefits are of using it in an integration layer or a Service Oriented (SOA) environment (linked article is in Dutch).

I’ve written my experiences in how to develop a CDM and how to use it at run time in three succeeding blog posts:

– part I: Standards & Guidelines

– part II: XML Namespace Standards

– part III: Dependency Management & Interface Tailoring

But first let us start with the beginning.

What is a Canonical Data Model?

The Canonical Data Model (CDM) is a data model that covers all data from connecting systems and/or partners. This does not mean the CDM is just a merge of all the data models. The way the data is modelled will be different from the connected data models, but still the CDM is able to contain all the data from the connecting data models. This means there is always a one way, unambiguous translation of data from the CDM to the connecting data model and vice versa.

A good metaphor for this in spoken languages is the Esperanto language. Each living, existing spoken language can be translated to the constructed Esperanto language and vice versa.

In a CDM data translation, the translation is not restricted to the way the data is modelled, but will also be a translation of the values of the data itself.

Example Data

Let’s take as an example the country values for the US and The Netherlands in four connecting data models. Three of these models are ‘based’ on the English language and the last one on the Dutch language. The first two data models are of type XML, the third one is CSV and the last one is a JSON type model:

-

<location>

<street>A-Street</street>

<number>123a</number>

<city>Atown</city>

<country>United States</country>

<continent>North America</continent>

</location>

<location>

<street>B-Straat</street>

<number>456b</number>

<city>Bdam</city>

<country>The Netherlands</country>

<continent>Europe</continent>

</location>

|

-

<Address

zip_code="93657">A-Street 123a, 93657, Atown</Address>

<Address

zip_code="1234 AB"

country_code="nl">B-Straat 456b, Bdam</Address>

|

-

Country;State;City;Street;Number;

USA;California;Atown;A-Street;123a;

NLD;;Bdam;B-Straat;456b;

|

-

{"adres":

{"landcode":1, "postcode":"93657", "woonplaats": "Atown", "straat": "A-Street", "nr":"123a"}

},

{"adres":

{"landcode":31, "postcode":"1234 AB", "woonplaats": "Bdam", "straat": "B-Straat", "nr":"456b"}

}

|

As you can see, there are not only four different ways of data modelling (two XML types, a CVS and a JSON type), but also four different values for the same country. The second example does not even have a value for the Unites States, because it defaults to "us”.

Despite of the differences, these examples of different data models contain the same information. When a CDM is defined, it should be able to contain all data of these models. Note that the data items continent, state and zipcode do not exist in all the data models. Also note that there is no value for state in case of a Dutch address (example 3).

P.S. There might even be more connecting systems that do not do anything with addresses, so their data model does not contain address data.

Creating a Canonical Data Model

When a CDM model is created, it is wise to be flexible and ready for future changes and extensions. Create a CDM that fits best in the integration software being used. Most likely this will be a XML type data model. However, JSON is increasingly supported by integration software and is becoming more popular because of its reduced size and the fact that is is used in front end technology, especially for mobile devices.

Let’s select XML for the CDM in this example and English based, which makes it easier in case non-Dutch developers have to work with it.

In our example the address data in our CDM can look like this:

<Addresses>

<Address>

<Street>A-Street</Street>

<Number>123a</Number>

<ZipCode>93657</ZipCode>

<City>Atown</City>

<State>California</State>

<CountryCode>US</CountryCode>

<ContinentCode>NA</ContinentCode>

</Address>

<Address>

<Street>B-Straat</Street>

<Number>456b</Number>

<ZipCode>1234 AB</ZipCode>

<City>Bdam</City>

<CountryCode>NL</CountryCode>

<ContinentCode>EU</ContinentCode>

</Address>

</Addresses>

|

For the technical reader: the definition of this XML fragment (XSD):

|

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34 |

<element

name="Addresses"

type="tns:tAddresses"/>

<complexType

name="Addresses">

<sequence>

<element

name="Address"

type="tns:tAddress"

minOccurs="0"

maxOccurs="unbounded"/>

</sequence>

</complexType>

<complexType

name="tAddress">

<sequence>

<element

name="Street"

type="string"

minOccurs="0"

maxOccurs="1"/>

<element

name="Number"

type="string"

minOccurs="0"

maxOccurs="1"/>

<element

name="ZipCode"

type="string"

minOccurs="0"

maxOccurs="1"/>

<element

name="City"

type="string"

minOccurs="0"

maxOccurs="1"/>

<element

name="State"

type="string"

minOccurs="0"

maxOccurs="1"/>

<element

name="CountryCode"

type="tns:tCountryCode"

minOccurs="0"

maxOccurs="1"/>

<element

name="ContinentCode"

type="tns:tContinentCode"

minOccurs="0"

maxOccurs="1"/>

</sequence>

</complexType>

<simpleType

name="tCountryCode">

<restriction

base="string">

<pattern

value="[A-Z]{2}"/>

</restriction>

</simpleType>

<simpleType

name="tContinentCode">

<restriction

base="string">

<enumeration

value="AF"/>

<enumeration

value="AN"/>

<enumeration

value="AS"/>

<enumeration

value="EU"/>

<enumeration

value="NA"/>

<enumeration

value="OC"/>

<enumeration

value="SA"/>

</restriction>

</simpleType>

|

This XML data structure (model) contains all the data items available in our examples. When it comes to flexibility, it is wise to use elements only and no attributes in XML. Usage of elements only makes the model more flexible and ready for future changes. Do not use ‘mixed content’ elements, meaning elements with data as well as child elements. An element is either a container element containing child elements or an element only containing data. Create a ‘plural container’ element for all elements that might (in future) occur more than once. Make the plural element single and obligated (min=1, max=1) and its child elements optional (min=0, max=unbounded). This keeps your model backwards compatible.

It is wise to have standards for the CDM and one person (or a group in a large project) who is responsible for maintaining the CDM model. In the XSD you can see that in this CDM example all the data elements are optional. You could argue there should at least be a street or a city. But what if there is a system that deals with addresses being created, so between the screens there is only half the data of an address present? Or a system that uses only a part or maybe even one data item of an address?

First benefit of using a CDM: Less translations

Now why would you introduce another extra data model, when you already have to deal with existing data models? Can’t we just choose one of them and use it as the central ‘canonical’ data model? Or can’t we just translate data of the existing data models when they connect to each other?

I will start with the last question. When there are only two systems that are connect to each other and there are no future plans to connect them with other systems, that is a good option. It is an overkill to introduc a CDM. But when there are three systems that connect to each other, you already benefit from a CDM. three systems have a maximum of 6 translations: A-B, B-C and C-A (and vice vers). When using an interconnecting CDM, you also have a maximum of 6 translations: A-CDM, B-CDM and C-CDM (and vice versa).

When there are more than three connecting systems, the difference in the number of translations between using a CDM or not increases fast in favor of using a CDM:

|

Number of translations |

| # systems |

without CDM |

with CDM |

| 3 |

6 |

6 |

| 4 |

12 |

8 |

| 5 |

20 |

10 |

| 6 |

30 |

12 |

| 7 |

42 |

14 |

| 8 |

56 |

16 |

Even when not all the systems are connect, the use of a CDM quickly results in less translations.

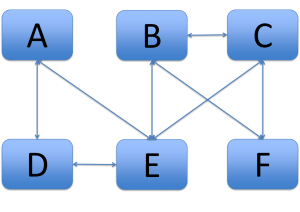

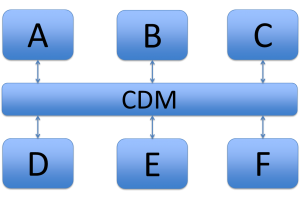

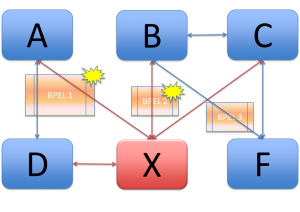

To give a graphical example of six connecting systems, but not all connecting with each other (it is even quite limited):

Connections without a CDM

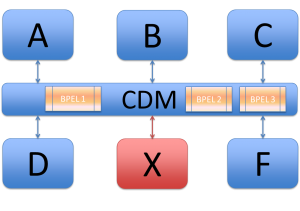

Connections with a CDM

In this example, you need 16 translations when you do not use a CDM. With a CDM , you need only 12.

Second benefit of using a CDM: Translation maintenance

There is a second reason for using a CDM related to translations. What happens when the data model of a connected system changes? For example when a system is replaced by another system or when a system is updated to a newer version. In the last case, the changes most likely will be minor, but still have to be checked at every connection point, so each translation, of that system.

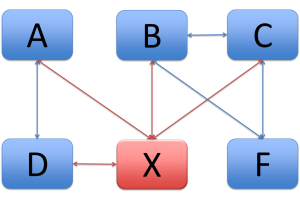

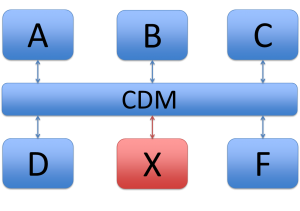

Let’s use the graphical picture above and assume that system E is replaced by system X.

When no CDM is used, there are four connections, with system A, B, C and D. This means there are 8 translations that have to be changed, two per system: to and from system X. For example when A is calling X, the request is a translation from A to X and the response from X to A. When a CDM is used, only two translations have to be changed: from CDM to X and from X to CDM.

Graphically explained:

Maintenance without a CDM

Maintenance with a CDM

Third benefit of using a CDM: Logic maintenance

Often the integration software that connects the systems, also has some logic or orchestration (e.g. with BPEL). For example: when a message from system A arrives and it is an order, then the order has to be routed to the ERP and to the financial system. And if the order is for a registered customer, the order has to be routed to the CRM system also. This kind of rules means there is some logic, the integration layer asks the CRM system if the customer of the order is a registered customer and depending on the answer, the order is routed to the CRM system or not. When this logic is using the data model of the connected systems, there is a dependency between the logic and the connecting system. So when one of the connecting systems changes, you need to check all logic to see if it uses (some part) of the data model of the connecting system. And if so, the logic has to be adjusted or rewritten. When a CMD is used, all logic (assume this is done right) is written with the data model of the CDM. Thus there is no dependency and a change of a connecting system does not affect the business logic in the integration layer.

Let’s take the previous pictures as example again and assume there is business logic written in BPEL at three places: business logic related to systems A, D and E, business logic related to systems B and E and business logic related to systems B and F. Now again: What happens when system E is replaced by system X. This means that BPEL1 and BPEL2 have to be adjusted or even rewritten (and tested) whereas with a CDM you do not have to do anything!

Graphically explained:

Logic maintenance without a CDM

Logic maintenance with a CDM

Existing Data model as CDM?

At the start of this blogpost, I raised the question whether an existing data model of a connecting system can be used as the CDM. In theory this is possible. Mostly there will be one large central system, most likely the ERP, that covers all or almost all kind of data. It may be tempting to use that model as the CDM. But what if somewhere in future the ERP is replaced by a new version. Even minor differences can cause problems. You might be tempted to take the old data model as the CDM and make translations from the new model to the CDM, the old data model. When using XML and the new and the old one have different namespaces, this is even possible. But still, you are bound to some old data model of an outdated system. Mostly that is not what you want. It might even cause problems with licenses, especially in case the system from which the data model it taken as CDM, is replaced by a system of another vendor.

Another disadvantage is that it could be confusing for developers of the system, especially future developer who are confronted with multiple data models of which two are quite similar. Mistakes are easily made. And what if a new system is connected and new data elements have to be added to the model. How flexible is it? Can it easily be changed and extended with backwards compatibility? That is why I advise to create your own CDM!

Conclusion

It is quite clear that using a Canonical Data Model in an integration layer or SOA environment soon pays off. You can summarize this into decoupling the external systems (by their data models) from the integration layer or SOA environment, so in fact decouple them from each other!

How do you do this? How do you setup a CDM which is flexible, so it can be changed and extended easily while being backward compatible? And the data model still should fit into interface descriptions of systems (wsdl) without getting too big, so it becomes, functionally seen, meaningless. This means it must be able to be tailored, so the interface (wsdl) reflects its functionality.

Another topic is standards and best practices about data, or specific XML, usage. Which standards are useful and why? When using XML, should you use a predefined XML ‘flavor’ like "Russian Doll”, "Venetian Blind”, "Salami Slice” or "Garden of Eden”? How about run time dependencies? Should you use a central run time CDM with versioning or only use a central design time CDM which does not exist at run time, but only acts as copy-paste reference for development? In my next blogpost I will share my experiences about these questions and give valuable advises which prevents problems we have run into.